We’re having: Matzo Balls! Gefilte Fish! Pink Horseradish! Overdone pot roast! And… Mead?

“Surely you must be mistaken, my fellow chosen person,” I hear you quip. “It says specifically – though admittedly a touch enigmatically – drip wine on your plate and say, ‘D’tzach Adash B’achav.’ It’s right there in backwards black-and-white!”

“Aha!” I retort, “You’re only thinking about the Seder! What about our 40 years in the wilderness? (…and by that I mean 8 days without beer.) Are we to survive on water and dessert-wine alone?”[1]

This is just the question which troubled our forebearers, it seems.

To lay it out simply, beer is made from grain and grain is not allowed during Passover. Wine had to be made under crazy strictures and the result was… usually less than satisfactory. Spirits, if they’re fruit based, may or may not be allowed, depending on who you ask. And water, for much of our history, was not safe to drink.

The answer to our thirsty trials comes to us from that great work of Semitic Literature The Complete American-Jewish Cookbook by Anne London and Bertha Kahn Bishov.[2] What’s most interesting about the recipe (included below) is not the recipe itself, but the curious historical tidbit which precedes it.

This amber liquid used to be a tradition during Passover. In the past two decades it has gradually disappeared so that the present generation is almost completely unaware of its existence. To revive this tradition, the following recipe is included, in the hope that it will again find its place among the favorites of the Hebrew People during Passover.

…

4. On all other nights we dine sitting upright or reclining. Why on this night do we all recline?

5. Why did you old people get to drink mead during Passover but we don’t? Huh? Hmmmm?

Alas, I feel as confident that we will receive a reply to this heartfelt query as I do to question 4. I firmly believe that I will go to my grave never knowing why we eat in a reclining position at the Seder (which we in fact do not), nor shall I ever know why mead lost its prestigious position at the dinner tables of the world during the 20th century.

Oh well, that doesn’t stop us from bringing it back. As we say ’round these parts, “Just one bottle of Mannaz all week? Dayenu!”

1. I know, I know… there are “good” Kosher for Passover wines, but seriously, we’re following regulations laid down by medieval rabbis who decided that people might get peanut butter confused with bread-dough. Just buy good wine and lie to your persnickety uncle.

2. Your Question: “You know that just being a book doesn’t make something literature, right?” My Answer: “Well, you find me a famous work by a Jewish author that doesn’t discuss food at a preposterous length or read like a cookbook.” Your response: “Touché.”

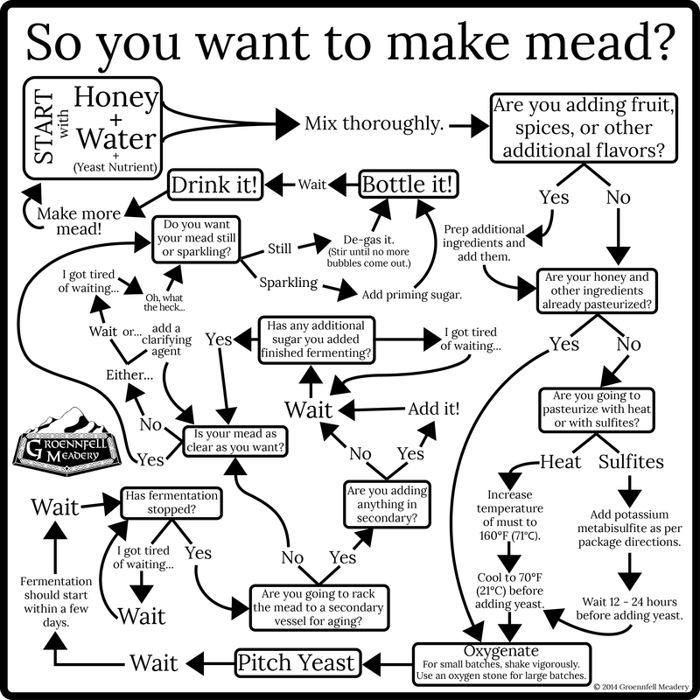

Here is The Recipe which we do not officially endorse since it lacks sanitation and, y’know… yeast.

Med (or Mead)

First you must purchase a small wooden keg or barrel with a spigot, and at least one yard of cheesecloth. Hops can be purchased at any “brew your own” beer and wine outfitter.

- 1/2 ounce hops

- 1/2 gallon honey

- 2 gallons water

- 1 lemon, sliced thin

Optional: 1/2 cup caramelized sugar to be added to med (after fermentation) to darken the color

Combine water and honey in a large pot, adding lemon and hops (tie hops in a piece of cheesecloth). Stir frequently and bring to a boil. Reduce heat to low, and cook for at least 1/2 hour. Skim frequently. Remove from heat. Let cool. When cool enough, strain through cheesecloth. If possible, strain directly into the wooden keg or barrel, being very careful to leave at least one quarter of the keg or barrel empty, to allow for fermentation. Store in a cool, dark place for at least 3 weeks. The liquid may then be removed from the keg into bottles, or left in the keg, as you wish. Remember: if a darker color is desired, caramelized sugar may be added to the med after fermentation.