Since we pride ourselves on being open-source, the brew-staff agreed that we couldn’t let our pride get in the way of sharing the story of our most frustrating month. It is also commonly agreed upon that more can be learned from a mistake than a success.

If you are unfamiliar with Valkyrie’s Choice, you should check out the recipe here as well as our general brewing practices.

Also, a spoiler alert: We did manage to rescue the batch, and we’re throwing a huge party to celebrate our success this weekend!

Here begins the saga of Valkyrie’s Choice.

Things that were the same as always:

- Water temperature

- Water filtering

- Nutrient addition

- Sulfite volume and timing

- Batch volume

- Honey quantity

- Oxygenation

- Wait-time after sulfiting

- Volume of yeast pitched

- Tank temperature

- Ambient temperature (which shouldn’t matter since the tank is insulated)

Things that were different:

- New honey from a few hours from our normal farm

Observations of note:

- The aroma of the must had a slightly vegetal aroma (somewhat like asparagus) which dissipated during pump-over. This is relatively common in light Canadian honey, but it does correlate with one other batch we had that failed to reach full attenuation (that one was 1.008 instead of 1.002).

- The time between pitching yeast and active fermentation was identical to our standards (about four hours for vigorous bubbling)

- The average rate of fermentation as observed by hydrometer and refractometer was completely normal for the first five days (about .010 gravity points per day aka 2.5 °P)

- Fermentation was on the same logarithmic arc we expect to see as it heads towards full attenuation

- The smell of the fermentation was perfectly normal with no vegetal aroma

- pH was completely normal.

Here’s where things start to go awry. After the normal period of active fermentation (about six days) the bubbling slowed as anticipated, the temperature in the tank began to drop due to lack of metabolic activity, and all seemed right with the world… until we tasted it.

The mead tasted fantastic! The only problem was that it was distinctly sweet. We took a gravity reading and found that it was at 1.024. At this point it should have been at 1.004 at the highest, ideally 1.002. We double-checked the reading with a refractometer with correction calculation and the reading was identical.

No big deal! We’ve dealt with this before. Besides, canning day was two weeks away.

Here’s what we tried, in order, with waiting period [and gravity in brackets next to it].

- Degassing through CO2 purge, 2 Days [No Change]

- Recirculation of yeast back into solution through pumping, 2 Days [1.024-1.020]

- Recirculation of yeast plus nutrient addition with the effect of degassing, 4 days [No Change]

- Reoxygenated, 2 Days [No Change]

At this point, the batch was officially stalled, there was no way to meet our canning date, and the state was days from running out of Valkyrie’s Choice.

At this point, Kelly sat the brew team down to go step-by-step through the process (“Did you accidentally add Sorbate?” “No.” “Are you sure?” “Pretty sure.” “Pretty sure is not OK.” “I’ll go check… No. No we didn’t.” “That’s too bad; then I could have just blamed this on you being idiots.”)

The next question was: “Have you tried absolutely everything?” Or, in other words, “If you had unlimited resources what would you do?”

The answer was simple: “I need $160 and two extra weeks.”

Our friends over at Iron Heart jumped through hoops to get us a new canning day, bless their hearts. So there was the two weeks we needed. Now, for the magic bullet.

There are thousands of yeast strains out there, but most brewers only use a handful. One of the best things about being a homebrewer is the ability to experiment on each and every batch. This is why we advocate that our brewing staff keep homebrewing as a hobby, even after they start working for us.

One of the strains that Ricky had used in the past is DV10 by Lalvin. He describes it as the SpecOps of yeast: It goes in where no one else can get the job done, and it does its work quickly, cleanly, and – under the best circumstances – you don’t even know that it’s been there.

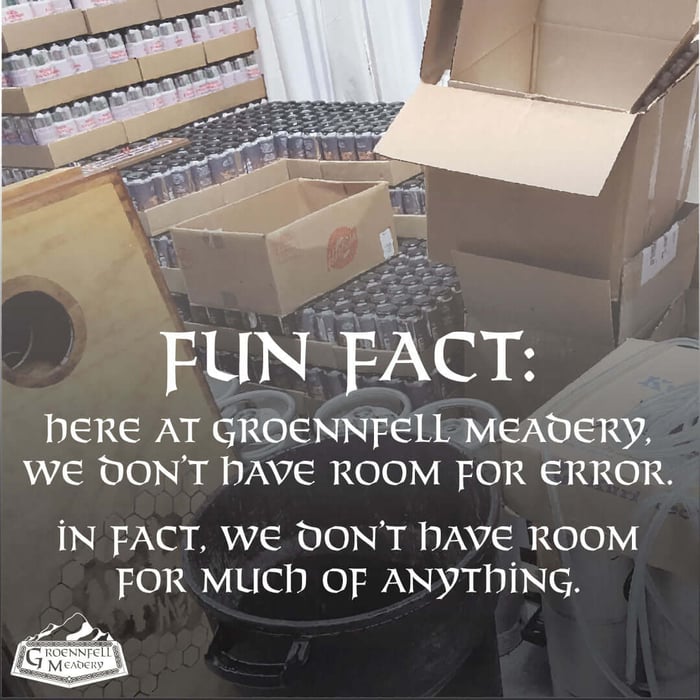

One hour after pitching a small amount (by commercial standards) of DV10, the bubbling had started again. Over the next week the fermentation followed a bell-curve of activity and after 8 days we were at our goal of 98% attenuation with a final gravity of 1.002.

The batch tastes amazing, the abv is spot-on, and carbonation is well under way!

Here are the big takeaways from our scary experience:

- The honey seems to be the only real variable here. The apiary we used also pollinates agricultural products (rapeseed, primarily), and there is a slight possibility that some of the honey came from this source. We have switched suppliers to another Canadian apiary that can guarantee the wildflower provenance of the honey.

- We are going to experiment with recirculating the yeast on a daily basis at the start of fermentation to see the effects on the health of the fermentation.

- We are always going to keep DV10 on-hand… just in case.