Well, for many meaderies yeast comes in a sterilized plastic container from a reputable company with an excellent track record of low infection rates. But that’s like saying that dogs come from the pet store (which would have made the very excellent Nova documentary Dogs Decoded much shorter). However, since yeast is one of the three essential ingredients for mead making, we’ll dig a little deeper.

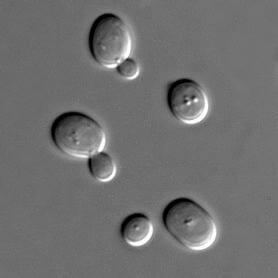

It is estimated that yeast comprises 1% of all fungal species on the planet.[1] It is found floating in the air, nestled on the skin of fruit, hanging out on the human body, and a trillion other places. In addition to these wild strains, there are cultivated strains primarily derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and also to a much lesser extent from Saccharomyces bayanus and Brettanomyces.[2] Each has its own nuances and raison d’être.

With thousands of species described and hundreds of strains available, how do we know which one to use? For our purposes, the primary function of yeast is to turn sugar into alcohol, carbon dioxide, and a few other components (fermentation), at a known rate (attenuation), in the high alcohol environment of mead (alcohol tolerance), then get the heck out of the way (flocculation).

At Groennfell Meadery, we prefer a dry mead strain. Using the terms above, this means that we like a yeast that: Ferments cleanly with very little ester or phenol production, has a very high attenuation and alcohol tolerance, and also a high rate of flocculation to produce a bright, pretty mead. To make sense of this, let’s take another common yeast strain to see how it stacks up. Hefeweizen Yeast ferments with a very high level of ester and phenol production with medium attenuation, low alcohol tolerance, and extremely low flocculation. This is why a good hefeweizen is slightly sweet with a distinctive banana and clove flavor; it rarely if ever has a high alcohol content, and is as cloudy as a London morning.

Just imagine if we used a porter yeast instead of a dry mead yeast! But we don’t. So now you know our secret formula. (Except for our honey source, how we treat our water, our fermentation conditions, our aging regimen, and our stabilization process.)